Agriculture formed the foundation of Muisca society, sustaining their communities and influencing their social, spiritual, and economic life. The Muisca of the Andean highlands in present-day Colombia developed sophisticated farming tools and techniques adapted to the mountainous terrain and variable climate. These innovations allowed them to cultivate maize, potatoes, quinoa, coca, and other essential crops while maintaining ecological balance. Understanding their agricultural practices provides insight into the Muisca’s ingenuity, resourcefulness, and deep connection with the land.

Table of Contents

Primary Farming Tools

- Coas: Long wooden digging sticks with pointed ends used for planting maize and tubers. The coa allowed farmers to prepare the soil efficiently in rocky or uneven terrain.

- Stone hoes: Tools made from sharpened stone attached to wooden handles for breaking ground, weeding, and leveling fields.

- Baskets and carrying tools: Woven from reeds and fibers, used to transport seeds, harvest, and manure.

- Water management tools: Wooden channels, canals, and clay containers enabled irrigation and storage of water, critical for terrace agriculture.

- Grinding stones (batán): Used to process grains like maize and quinoa, demonstrating an integrated approach from cultivation to food preparation.

| Tool | Material | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Coa (digging stick) | Wood | Planting seeds, turning soil |

| Stone hoe | Stone and wood | Breaking ground, weeding, and field maintenance |

| Baskets | Reeds/fibers | Transporting seeds, crops, and fertilizers |

| Water channels | Wood/clay | Irrigation and drainage |

| Grinding stone (batán) | Stone | Processing harvested grains |

Farming Techniques

- Terracing: The Muisca carved stepped terraces into hillsides to prevent erosion, retain water, and maximize arable land.

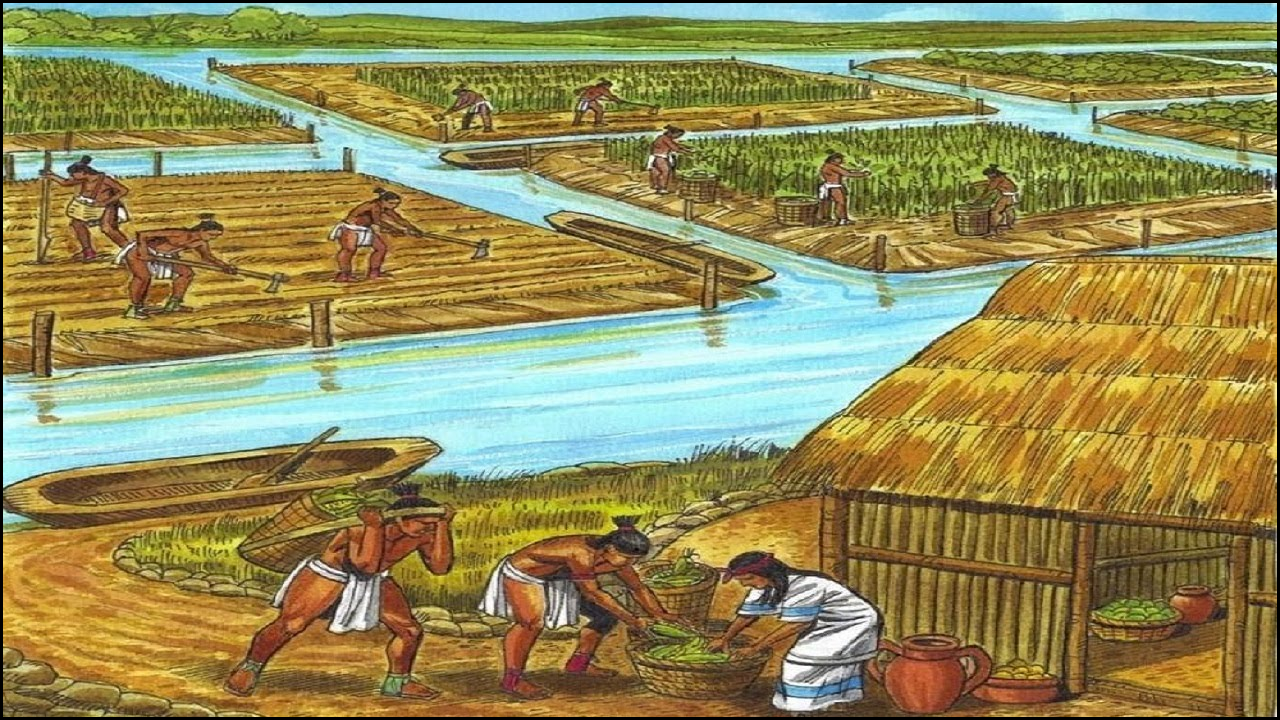

- Raised fields (camellones): Elevated planting areas improved drainage, soil fertility, and crop yields in marshy regions.

- Crop rotation and polyculture: Maize, beans, quinoa, and potatoes were grown together, reducing soil depletion and increasing productivity.

- Irrigation: Canals, channels, and lakes were utilized to control water distribution, particularly during dry seasons.

- Soil enrichment: Organic matter, such as plant residues and animal manure, was added to enhance fertility and sustain yields.

Sacred and Ritualized Agriculture

- Agriculture was inseparable from religion and ritual practice.

- Planting and harvest times were determined according to lunar phases and solar positions, reflecting cosmic guidance.

- Offerings to lake spirits, mountains, and deities ensured crop fertility and protection from natural calamities.

- Ceremonial use of tools, such as coas and batáns, reinforced the sacred dimension of cultivation.

- Rituals strengthened community bonds and ethical stewardship, integrating spiritual care into practical farming.

| Farming Practice | Practical Purpose | Spiritual/Communal Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Terracing | Prevent soil erosion, maximize land use | Aligns with sacred geography, terraces considered sacred spaces |

| Raised fields | Improve drainage and fertility | Offered the first produce to the deities for blessing |

| Crop rotation | Maintain soil health | Honors the cyclical nature of life and seasons |

| Irrigation | Ensure water supply | Invokes lake and river spirits for abundance |

| Manure enrichment | Increase fertility | Symbolic reciprocity with Earth spirits |

Crops and Their Cultivation

- Maize: Staple food, planted during the waxing moon for optimal growth; requires frequent weeding and soil maintenance.

- Potatoes: Grown in terraced fields to utilize slopes efficiently; suited for cooler microclimates.

- Quinoa: High-altitude crop cultivated on well-drained terraces, providing nutritional and ceremonial value.

- Coca: Cultivated for medicinal and ritual purposes, often grown near sacred sites.

- Tubers and legumes: Complemented staple crops, ensuring dietary diversity and soil enrichment.

Community and Labor Organization

- Farming was largely a collective activity, with families and communities working together.

- Leaders and elders coordinated labor, tool distribution, and field planning.

- Labor divisions were partly based on gender and age, with men handling heavier tools and women participating in planting, weeding, and harvesting.

- Festivals marked key agricultural milestones, promoting community cohesion and spiritual observance.

- Communal labor ensured efficient use of resources and sustainable farming practices.

| Community Role | Responsibilities | Relation to Farming |

|---|---|---|

| Zipa/Zaque | Oversight of territory and festivals | Ensured sacred alignment of agriculture |

| Priests (Chyquy) | Ritual leadership and cosmic guidance | Timing planting and harvest ceremonies |

| Men | Heavy field work | Digging, terrace construction, and irrigation |

| Women | Seed planting, harvesting, food processing | Ensured continuous production and ritual offerings |

| Elders | Knowledge transmission | Maintaining agricultural techniques and ethical norms |

Sustainability and Environmental Adaptation

- Techniques like terracing, raised fields, and polyculture reflect Muisca awareness of environmental limitations.

- Irrigation and water management minimized drought risk and optimized crop growth.

- Crop diversity and soil enrichment practices prevented depletion and maintained long-term fertility.

- Sacred rituals reinforced the ethical treatment of land, rivers, and forests, promoting ecological balance.

- The Muisca model demonstrates integration of technology, spirituality, and sustainability in pre-Columbian agriculture.

Legacy of Muisca Farming Practices

- Many Muisca agricultural techniques influenced later indigenous communities in Colombia.

- Archaeological evidence of terraces, raised fields, and irrigation channels highlights their technological sophistication.

- Modern studies recognize the Muisca approach as an early example of sustainable highland agriculture.

- Sacred integration of agriculture with ritual and community life provides lessons for cultural and ecological sustainability today.

- The legacy underscores the interconnectedness of environment, spirituality, and human labor in ancient societies.

Closing Reflections

The ancient farming tools and techniques of the Muisca reflect a civilization that combined practical ingenuity with spiritual reverence for the land. Through tools like coas, stone hoes, and irrigation channels, and techniques such as terracing, crop rotation, and polyculture, the Muisca achieved agricultural efficiency and ecological balance. These practices were deeply intertwined with rituals, offerings, and communal labor, highlighting a worldview in which farming was both a sacred duty and a social responsibility. The Muisca legacy offers a model of sustainable, spiritually informed agriculture that remains relevant in understanding human-environment interactions.