The ancient Muisca people of Colombia, part of the broader Chibcha cultural family, viewed the moon not merely as a celestial body but as a spiritual entity that governed the rhythm of existence. In Chibcha cosmology, the moon represented fertility, time, emotion, and the feminine principle—a symbol of both creation and transformation. Its cycles were closely linked to agricultural activities, social rituals, and moral balance, reflecting the belief that the universe operated through harmony between opposites. The moon’s influence extended far beyond the night sky; it shaped how the Muisca understood life, death, and the moral order that connected humans with the divine.

Table of Contents

The Moon as a Cosmic Balance

- The Chibcha worldview emphasized dualism, where every element of the cosmos existed in balance with its counterpart.

- The moon complemented the sun (Sué), together maintaining the equilibrium of day and night, masculine and feminine, order and chaos.

- This celestial duality represented the sacred interdependence of opposing forces, essential for sustaining life and moral harmony.

- The moon’s light was believed to illuminate the path of the spirit, guiding humans through moral and emotional darkness.

- Chibcha priests (chyquy) interpreted lunar phases to understand divine will and cosmic messages.

Cosmic Duality in Chibcha Belief

| Element | Masculine (Sun) | Feminine (Moon) |

|---|---|---|

| Deity | Sué | Chía / Huitaca |

| Symbolism | Light, order, rationality | Emotion, fertility, intuition |

| Time Cycle | Day, stability | Night, transformation |

| Energy Type | Active, solar | Receptive, lunar |

| Moral Principle | Law and structure | Compassion and freedom |

The Moon as the Feminine Principle

- The moon symbolized the essence of womanhood, mirroring the cycles of fertility and transformation in the female body.

- Lunar deities such as Chía and Huitaca embodied contrasting aspects of femininity — one nurturing, the other rebellious.

- Women’s lives and rituals were often synchronized with the moon’s phases, especially in matters of birth, growth, and renewal.

- The waxing moon was associated with growth and fertility, while the waning moon represented cleansing and reflection.

- The moon’s spiritual power was seen as gentle yet potent, capable of influencing crops, emotions, and the tides of destiny.

Chía: The Guardian of Light and Order

- Chía was the primary lunar goddess in Chibcha mythology, representing purity, love, and maternal care.

- Her worship centered around the temple city of Chía, where rituals celebrated the moon’s protective influence.

- She was the consort of Sué, creating a divine partnership that symbolized cosmic balance.

- The Chibcha believed that her lunar light nurtured the earth and ensured fertility, vital for agricultural prosperity.

- Priests used the moon’s cycles under her name to determine sowing, harvesting, and religious ceremonies.

Attributes of Chía

| Aspect | Description |

|---|---|

| Role | Goddess of the moon, fertility, and harmony |

| Partner | Sué, the Sun god |

| Temple | Located in the city of Chía, near Bacatá (Bogotá) |

| Symbol | Crescent moon and silver light |

| Cultural Function | Maintained cosmic and moral order |

Huitaca: The Shadowed Moon and Rebellion

- The goddess Huitaca represented the moon’s darker and more sensual side.

- She symbolized pleasure, wisdom, and defiance, encouraging people to live freely and joyfully.

- Her story reflects the spiritual tension between freedom and order within Chibcha thought.

- Huitaca’s conflict with the moral teacher Bochica led to her transformation into an owl, linking her with nocturnal wisdom.

- Her association with the moon’s hidden side expressed the complexity of the human spirit, acknowledging that light and darkness coexist in all beings.

Symbolic Comparison of Chía and Huitaca

| Attribute | Chía | Huitaca |

|---|---|---|

| Nature | Benevolent and orderly | Rebellious and free-spirited |

| Symbol | Crescent moon | Full moon or owl |

| Energy | Nurturing and protective | Transformative and passionate |

| Moral Aspect | Harmony and discipline | Desire and independence |

| Spiritual Meaning | Balance and creation | Wisdom through defiance |

Lunar Cycles and the Passage of Time

- The Muisca calendar, based on Chibcha cosmology, relied heavily on lunar observations to measure time.

- The year was divided into lunar months, each guiding agricultural and ritual activities.

- New moons marked beginnings, ideal for planting and renewal, while full moons were times of celebration and thanksgiving.

- The waning moon symbolized reflection and endings, often linked with purification rituals.

- This connection between time and the moon reinforced the idea that existence followed a cyclical pattern, mirroring birth, growth, decay, and rebirth.

Spiritual Meaning of Lunar Phases

| Lunar Phase | Spiritual Significance | Associated Activities |

|---|---|---|

| New Moon | Renewal and creation | Planting, new projects |

| Waxing Moon | Growth and fertility | Agricultural expansion, childbirth rituals |

| Full Moon | Celebration and abundance | Festivals, offerings to deities |

| Waning Moon | Cleansing and wisdom | Reflection, purification ceremonies |

The Moon and Agricultural Rituals

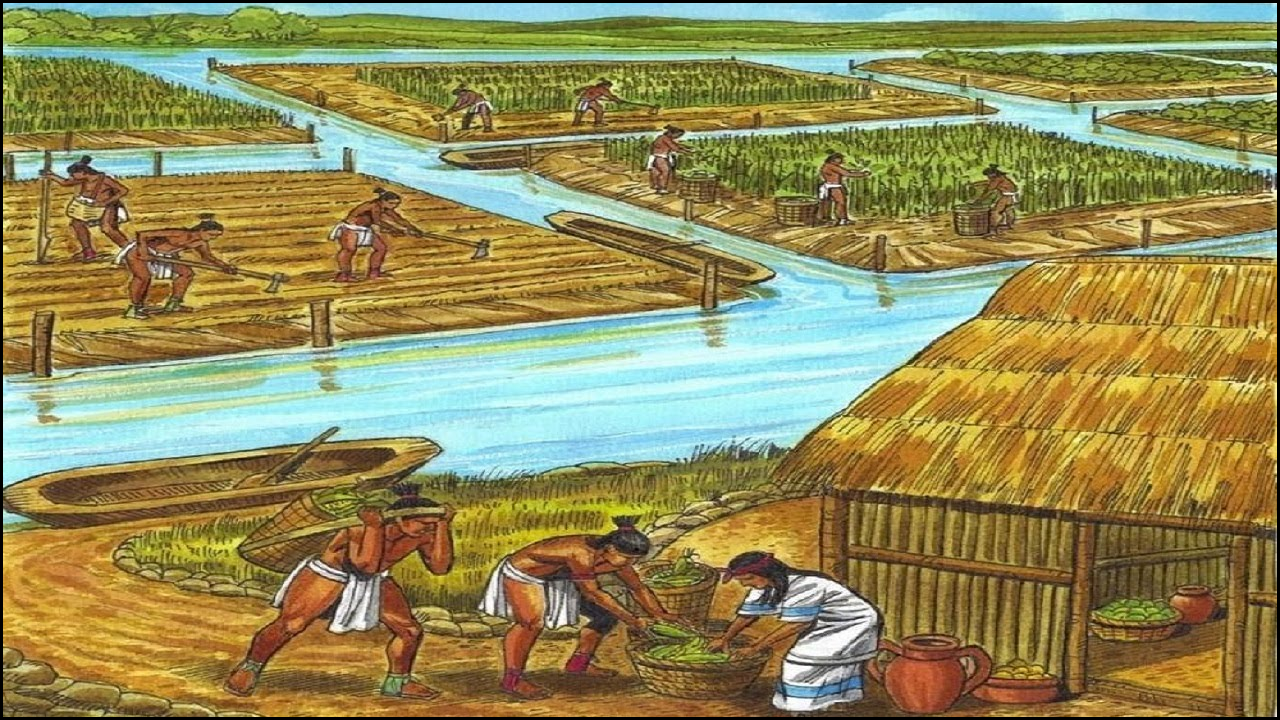

- The Chibcha people lived in a region of high plateaus and fertile valleys, making lunar cycles crucial for farming.

- Priests observed the moon to determine when to sow seeds or harvest crops, ensuring alignment with divine rhythm.

- Offerings of gold, corn, and chicha (fermented drink) were made during full moons to thank the goddess for abundance.

- Ritual dances under moonlight symbolized fertility and the union of heaven and earth.

- The moon’s phases also determined times of fasting or rest, reinforcing spiritual discipline in the community.

Moral and Spiritual Lessons of the Moon

- The moon represented the inner world of emotion, intuition, and reflection.

- Its waxing and waning served as a metaphor for human growth, teaching that all joy and suffering are temporary.

- The Chibcha believed that spiritual strength came from accepting change and impermanence, just as the moon constantly transformed.

- Myths of Chía’s harmony and Huitaca’s rebellion reminded people of the need for balance between control and freedom.

- The moon, therefore, acted as both a guide and a mirror, helping individuals align with cosmic order and self-awareness.

The Moon as a Guide for the Soul

- After death, the Chibcha belief held that the soul journeyed through cosmic pathways illuminated by the moon.

- The moon’s silver light represented spiritual purification, guiding souls to the next realm.

- Lunar symbols were often used in burial ornaments, emphasizing rebirth and protection in the afterlife.

- Shamans invoked lunar power to connect with ancestral spirits and divine wisdom during night rituals.

- The moon thus functioned as a bridge between the earthly and spiritual worlds, linking mortals with the eternal.

Integration of Moon Worship in Daily Life

- The Muisca synchronized social, economic, and religious life with lunar movements.

- Marriage ceremonies, harvest festivals, and purification rites were all planned according to the lunar calendar.

- Moonlight was viewed as a blessing for conception and healing, particularly for women.

- The goddess’s influence was present in music, art, and architecture, where circular and crescent motifs symbolized unity and continuity.

- The constant observation of the moon cultivated a deep spiritual discipline, reminding the community of their connection to cosmic cycles.

Enduring Legacy in Modern Culture

- The spiritual reverence for the moon survives in Colombian folklore, festivals, and oral traditions.

- Many highland communities still refer to the moon when predicting weather and agricultural patterns.

- Huitaca and Chía remain powerful cultural symbols of femininity, wisdom, and transformation.

- Modern artists and writers reinterpret these myths as expressions of identity, nature, and freedom.

- The moon continues to embody the spiritual heart of the Andes, linking past and present through timeless cycles.

Closing Perspectives

The moon in Chibcha cosmology was far more than a celestial light—it was the embodiment of the spiritual order that governed life itself. It symbolized the eternal rhythm of creation and destruction, harmony and defiance, life and death. Through deities like Chía and Huitaca, the Muisca people found meaning in the moon’s changing face, learning lessons of balance, renewal, and self-discovery. The moon guided their crops, their rituals, and their souls, serving as a bridge between the human and the divine. In its luminous and shadowed forms, the moon remains a timeless symbol of spiritual balance and the cyclical truth of existence in Chibcha belief.