Orchards and fields held profound symbolic meaning in Chibcha beliefs, representing more than physical spaces for cultivation. These landscapes embodied fertility, prosperity, spiritual connection, and social responsibility. The Muisca people of the Cundiboyacense Plateau perceived cultivated land as a living entity intertwined with deities, ancestors, and natural forces, reflecting their deep ecological and cosmological understanding. Orchards and fields were both practical and sacred, forming the foundation of sustenance, ritual, and cultural identity.

Table of Contents

Orchards as Symbols of Fertility and Abundance

- Orchards represented controlled fertility, where fruit trees, coca, and medicinal plants were carefully cultivated.

- They symbolized prosperity and wealth, often linked to the generosity of deities such as Chiminigagua (the Supreme Being) and Bachué (the Mother Goddess).

- Orchards were associated with ritual offerings, including fruits and sacred plants, to maintain harmony between humans and spiritual forces.

- Their structure reflected cosmic order, with rows and planting patterns aligned to optimize growth and spiritual significance.

- Orchards served as spaces for teaching agricultural and spiritual knowledge, passing ancestral wisdom to younger generations.

| Orchard Feature | Symbolic Meaning | Practical Function |

|---|---|---|

| Fruit trees | Fertility, life, and abundance | Food production and trade |

| Sacred plants (coca, medicinal herbs) | Spiritual connection and healing | Ritual use and medicine |

| Row patterns and alignment | Cosmic order and harmony | Efficient cultivation and soil preservation |

| Offerings and libations | Reciprocity with spirits | Protection of crops and land |

| Shade trees | Sustenance and nurturing | Soil fertility and microclimate regulation |

Fields as Symbols of Sustenance and Community

- Fields represented collective responsibility, where families and communities collaborated to cultivate maize, potatoes, quinoa, and legumes.

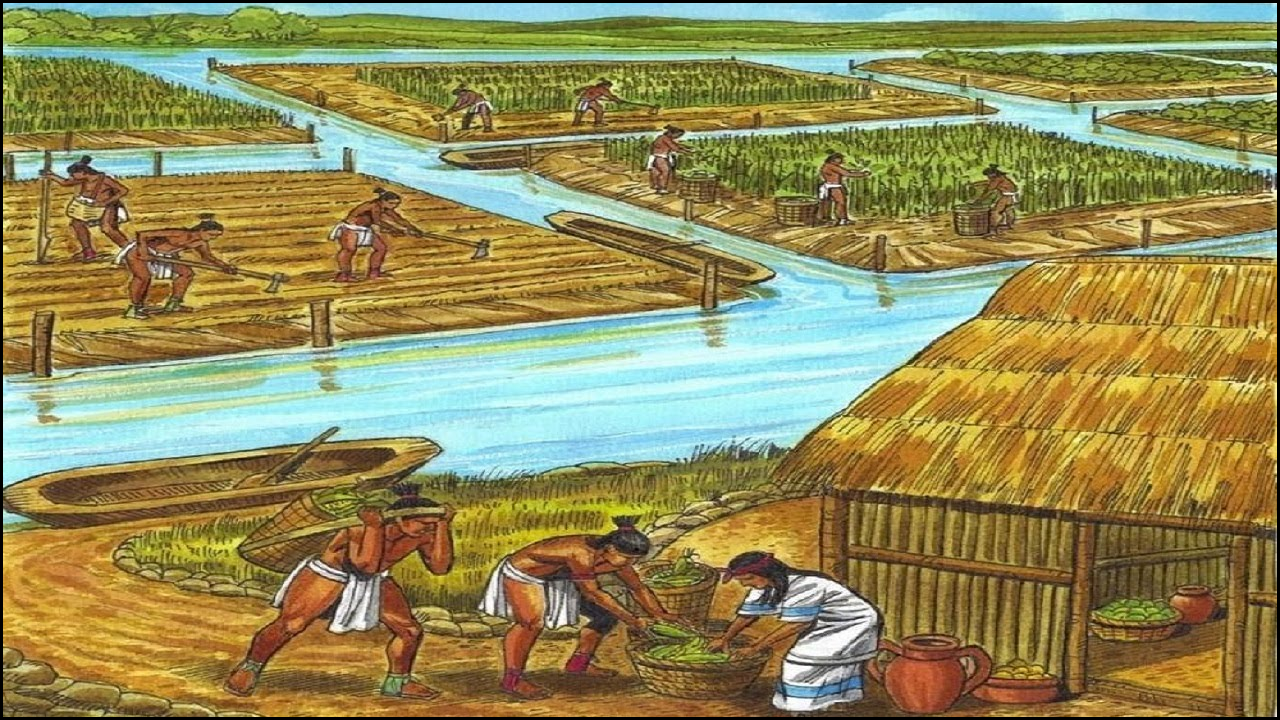

- They symbolized human ingenuity and adaptation, especially in terraces and raised fields, demonstrating environmental mastery.

- Fields were sites of ritual planting and harvest ceremonies, integrating agricultural labor with spiritual observance.

- They embodied temporal cycles, reflecting seasonal and lunar rhythms crucial for fertility and productivity.

- Through communal labor, fields reinforced social cohesion, ethical stewardship, and reciprocity with nature.

| Field Aspect | Symbolic Meaning | Agricultural Role |

|---|---|---|

| Terraces | Human-environment harmony | Soil conservation and crop yield |

| Raised fields | Innovation and adaptability | Drainage, fertility, and protection from floods |

| Seasonal crops | Life cycles and cosmic order | Ensures balanced nutrition and soil health |

| Communal labor | Cooperation and social responsibility | Efficient cultivation and resource management |

| Offerings to deities | Fertility and divine favor | Enhances productivity and spiritual protection |

Spiritual and Ritual Significance

- Orchards and fields were sites for planting rituals, first-fruit offerings, and harvest festivals.

- Offerings often included gold tunjos, chicha, and seeds, demonstrating reciprocity with nature spirits.

- Ritual calendars were guided by lunar phases, solstices, and celestial observations, ensuring harmony with environmental cycles.

- Sacred landscapes reinforced ethical and spiritual duties, teaching that human prosperity depended on respect for land and divine forces.

- Ancestors and deities were believed to inhabit orchards and fields, making stewardship a moral and spiritual imperative.

Orchards and Fields as Educational Spaces

- These spaces served as living classrooms, teaching agricultural skills, spiritual values, and ethical land management.

- Elders and priests (chyquy) guided youth in planting techniques, crop rotation, and ritual practices, preserving ecological and cultural knowledge.

- Observation of natural phenomena, like soil fertility and rainfall, integrated empirical knowledge with spiritual understanding.

- Cultural transmission ensured the continuity of sustainable practices and cosmological beliefs.

| Educational Role | Knowledge Imparted | Cultural Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Practical farming | Soil management, crop rotation | Food security and sustainability |

| Ritual practice | Offerings, timing, and ceremonial rites | Spiritual literacy and ethical stewardship |

| Environmental observation | Rainfall, lunar cycles, soil quality | Adaptive ecological knowledge |

| Community labor | Cooperation, responsibility | Social cohesion and shared prosperity |

| Ancestral guidance | Oral histories and myths | Preservation of identity and heritage |

Integration of Ecology and Spirituality

- Orchards and fields reflect a holistic worldview, where agriculture, ecology, and spirituality intersect.

- The Muisca recognized that fertility depended on both human effort and spiritual favor, linking ecological success to ritual propriety.

- Sacred and productive landscapes fostered biodiversity, soil conservation, and sustainable harvests.

- Agricultural spaces reinforced the principle of reciprocity, ensuring that land and human society thrived together.

- By embedding spirituality in cultivation, the Muisca maintained long-term ecological balance and social cohesion.

Legacy and Modern Relevance

- Archaeological evidence of terraces, raised fields, and ceremonial orchards shows advanced agricultural and spiritual integration.

- Modern agroecology and permaculture draw inspiration from Muisca practices of sustainability and sacred stewardship.

- Recognizing the symbolic and functional role of orchards and fields informs cultural heritage preservation and ecological planning.

- Indigenous perspectives highlight the importance of ethics, ritual, and knowledge transmission in sustainable agriculture.

- Orchards and fields exemplify how food production, spirituality, and community responsibility can coexist harmoniously.

Closing Perspectives

Orchards and fields in Chibcha beliefs symbolize more than cultivation; they represent fertility, spiritual connection, and communal responsibility. The Muisca integrated practical farming with ritual, ecological knowledge, and ethical stewardship, creating landscapes that were both productive and sacred. These agricultural spaces served as sites of education, spirituality, and social cohesion, demonstrating a holistic understanding of sustainability. The symbolism of orchards and fields continues to inspire modern approaches to agriculture, ecology, and cultural preservation, emphasizing the inseparable link between land, spirit, and community.